Zviad Dolidze. The Unknown Masterpiece of Georgian Silent Cinema

Georgia is a small country, but the local filmmakers are famous for their flawless films. In the 1970s of the last century, this circumstance gave the cause to the critics in the Soviet Union and in the rest of the world to bring into circulation the definition “The Phenomenon of the Georgian Cinema.” 1

“My Grandmother” (“Chemi Bebia”) was filmed in 1928, and the demonstration of it was scheduled for January of the next year, 1929. It was the directorial debut of a young filmmaker, Konstantine (aka Kote) Miqaberidze, who had experience working in theater and film. In 1921, he was shot in a supporting role in the first Georgian Soviet film "Arsena Georgiashvili". After this, he was invited to the other films for main roles, where he created the fully dramatic cinematic images. In some of them, he played in partnership with the Georgian film star woman, Nato Vachnadze. The filmgoers liked their duet very much.

Kote Miqaberidze perfectly performed the tricks, did his make-up himself, worked as an assistant to the director, was an excellent painter, studied the principles of film dramaturgy, and often was a guest of the film laboratory for clarification of the process of treatment of the film. He thought that if the film artist is not close to his people, he will never be able to create a realistic work that must respond to the contemporary challenges. If this artist is cooled at one point and falls behind in contemporary life, the people may forget him and put him on a list of powerless human beings. He liked to say that “the main thing is morality. When morality deteriorates, everything deteriorates: the house is not built, the land does not produce crops, the fruits do not grow.” 2

In the second half of the 1920s, the Georgian actors were invited to test their talents in film directing. They had some practice assisting directors, and that's why they were assigned to the position of filmmaker. Moreover, at that time, there was no film school in Georgia for teaching the professional skills of film directing. Among them was Kote Miqaberidze, and of course, he was more than happy for such an appointment. In his memoirs, he wrote:

“I was directing a satirical film, the aim of which was to denounce and deride bureaucracy, petty bourgeoisie, and protectionism. With these aims in mind, I was trying to discover new and sharp ways of cinematic expression because a simple “slavish illustration” of the script was not satisfying for me as a creative person.

With the writer Giorgi Mdivani, we wrote a script entitled “My Grandmother.” I later made a satirical film based on this script in 1928.

”Bebia” (aka “grandmother”), generally speaking, has no gender. This grandmother would be either a woman or a man. It means “protector.”

“If you have a grandmother, you will succeed,” says one of the characters in this film.

During the directing of this complicated film, I tried to distance myself from literature and stage adaptations. I was trying to be faithful to the principle of using the infinite possibilities of cinema to bring to life the director's and the scriptwriter's ideas.

These technical possibilities gave me, as a director, the opportunity to express the satirical content of this film and to make the social comedy that “My Grandmother” later became.” 3

The word “grandmother” (“bebia”) was used figuratively, meaning a person who pulled strings for someone. The main character of the film is dismissed and tries to find a “grandmother”, who promises to assist him in finding a new job but, in fact, makes things worse. This satirical comedy mocked the bureaucratic system. The authors reflected their contemporary lives, laziness, and neglect of duties in an original manner. 4

The film crew was very international. It included the Georgians, the Russians, the Armenians, and, what is most interesting, the Poles as well. The film cameramen, Anton Polikevich and Vladislav (according to another source, Vladimir) Poznan, were both Poles. The first was born in Lithuania, and the second in Poland. Polikevich lived in Tbilisi from 1913. He worked in the photo studio and then at the Pavel Pirone Film Company. Since 1924, he has been a cameraman for feature and documentary films. He made many Georgian films and was awarded the rank of the Honored Artist of Georgia. Poznan worked at the Pavel Pirone Company, and like Polikevich, since 1924, went to the film industry as a cameraman. He shot many Georgian films too.

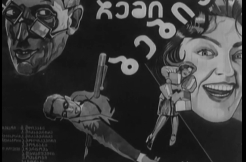

In the preparation period, Miqaberidze had worked vigorously, and sometimes, in the evenings, he invited his crew members to his house for working on the script and the budget. They wanted to write everything clearly and in detail. The new filmmaker desired to present his debut film suitably and worked energetically. He had painted one of the posters of the film, selected the sets long ago, and neatly prepared the interiors. In this film, Miqaberidze was the first to use animation in Georgian cinema, giving the most importance to the satirical character of the film. He invited Irakli Gamrekeli, an eminent stage designer and one of the founders of Georgian theatrical design, to take on the position of production designer. Gamrekeli had no connection to the cinema before.

When “My Grandmother” was realized, it attracted a lot of people, but after a few days, by order of the government, it was removed from the movie theaters and banned. The film was accused of formalism as an “anti-Soviet work”. In the anonymous letter that was sent to the State Security Department, someone wrote that this film was inspired by the Trotsky aspiration because the entire system of state management is shown as an absurdity and that such an attitude had had a negative impact on the political life of the Soviet citizens. Also, it was noted that the film's authors had encouraged establishing the worker's control over the state system, which was one of the key provisions of Trotsky's political program. That was the period of a broader campaign against Lev Trotsky, which ended with his exile from the Soviet Union. So "My Grandmother" was sacrificed to this campaign.

Fortunately, the film authors had survived the repression. The Soviet government was only limited by the above-mentioned act. Soon, Giorgi Mdivani moved to Moscow and became one of the most successful scriptwriters of Soviet cinema. Kote Miqaberidze continued his work as a film director. He had made a couple of documentaries and feature films. Later, he became interested in the animation. In 1956, because of the political developments in the Soviet Union, he sent a protest letter to Nikita Khrushchev. This was considered an anti-state act, and Miqaberidze was arrested. After three years, he was released and restored to his old workplace. Until his death, he worked at the film studio “Qartuli Filmi” (“Georgian Film”) as a director of the dubbing department. He died suddenly in 1973, when at the Tbilisi Film House he attended the memorial event dedicated to his friend and colleague (who committed suicide). Kote Miqaberidze made a speech, had called other colleagues for more support and kindness toward each other, arrived back from the stage, sat in the chair, and...

“My Grandmother” was banned for 39 years. In 1968, at the Moscow movie theater "Illusion," its premiere was held. The film-goers were admired. The film was announced as a masterpiece of Soviet cinema. In 1976, “My Grandmother” was restored. That gave us an opportunity to demonstrate it at movie theaters and international film festivals. Foreign film critics were amazed by this film. They did not expect such original cinematic thinking from the representatives of the Soviet cinema of the 1920s.

In the same year, London hosted the Georgian Film Festival. It was the first big retrospective of Georgian cinema abroad. The organizers of this event were the British Film Institute and its scientific worker, John Gillett, who was named a walking encyclopedia of film knowledge. Gillett arrived in Tbilisi himself to select the films. He put “My Grandmother” in the program. Later he wrote in the British press: “For the most people, Georgia is a little wonderful tourist area somewhere in Russia, famous for its wine and as the birthplace of Stalin. The Georgian films always remained in the shadow of the works of Moscow and Leningrad film studios, but after my visit to Georgia, I understood that Georgian cinema has absolutely different traditions and history.” 5

Gillett highly appreciated the film of Miqaberidze, indicated that it was a discovery for him because of its anti-bureaucratic satire and expressionistic décor, and declared that the several episodes were staged in the characteristic sharp style of the comedies of Mack Sennett.

“My Grandmother” was put in all the programs of the Georgian films that were presented in the United States, Germany, France, Great Britain, etc. In 2004, it was screened in Prague (Czech Republic) in a non-commercial movie theater where the original musical score was played magnificently by an American band. Two years ago, when this film was presented at the Georgian Film Festival in St. Petersburg (Russia), after the screening, one state functionary woman announced that over the last few decades, nothing has changed in her country and everything is the same as in this film.

There are two opinions about this film in Georgian film criticism. Some argue that Miqaberidze was influenced by German expressionism. They explain that fact by the popularity of this trend of art in Georgia in the 1920s. There were translated and published articles, poems, and short stories by German expressionists; the expressionistic performances were staged in the Georgian theaters; the local artists had drawn the expressionistic canvas, etc. 6 Thus, the filmmaker used conventional scenery, contrasting lights, and extraordinary perspective. The other part of the critics thinks that the main pathos of the film, the monumental forms of the heroes, the straightforwardness of the narration, and the general visual structure were created by the influence of Futurism and Constructivism because the production designer of this film was basically more constructivist and futurist than expressionist. 7

Of course, both positions are acceptable, but “My Grandmother” is not just a reflection of those trends mentioned above; it is also an expression of all modes of avant-garde cinema of those years. For example, in certain episodes of the film, there are several surrealistic passages, and this was during a period when Luis Bunuel's “Un Chien Andalou” did not yet exist. Miqaberidze shot the tricks masterfully and kept the rhythm from the beginning to the end, which is so organic for comedies like that. Because of his rich imagination, he obviously could not fit within the framework of this film, and that's why he referred to the documentary and animation elements too.

The debut film of Kote Miqaberidze was “a scathingly witty and aesthetically adventurous attack on the Georgian variant of the bureaucratic deviation known as “protectionism,” which dropped into the bottomless pit of forgotten films” 8

“My Grandmother” is one of the best examples of experimental cinema. It was called “The Satirical Phantasmagoria”, “The Shadowed Grotesque”, and sometimes “The Celebration of the Black Humor”. In sum If we take the fact that Kote Miqaberidze was a quite good caricaturist, we can name this work the sensible and splendidly revivalist cinematic caricature against the bureaucracy, which is very easy to perceive and understand for every representative of every nation.

Notes:

1 Menashe, Louis. Moscow Believes in Tears: Russians and Their Movies. Washington: New Academia Publishing, 2010, p. 325.

2 Kveselava, Rezo. Memories about Georgian Film Masters. Tbilisi: Saga, 2008, p. 114 (in Georgian).

3 Dumbadze, Soso and Nino Dzandzava (ed.). Kote Miqaberidze. Tbilisi: Sa.Ga., 2017, p. 141 (in Georgian).

4 Tsereteli, Kora. Famous Names. Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 1986, p. 71 (in Georgian).

5 Gvelesiani, Tatiana. The Main – They are Full of Life. Magazine “Akhali Filmebi”, 1976, #9, p. 4 (in Georgian and Russian).

6 Amiredjibi, Natia. The screen of Times. Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 1990, p. 145-146 (in Georgian).

7 Levanidze, Maia. German Expressionism, “Symphony of Horrors” and Kote Miqaberidze's “My Grandmother”, in collection: Art Processes. 1900-1930. Tbilisi: Kentavri, 2011, p. 169 (in Georgian).

8 Youngblood, Denise. "We don't know what to laugh at": Comedy and Satire in Soviet Cinema (from The Miracle Worker to St. Jorgen's Feast Day), in collection: Inside Soviet Film Satire: Laughter with a Lash (Andrew Horton, ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 43.